I’ve been aware that the amount of free gigabits I have available for this blog is gradually diminishing. I probably have a year or so left. But nevertheless I’ve taken the plunge and moved to my own domain:

So any bookmark or link to the old site will need to be changed. Or if you have opted for email notifications then that option will need renewing.

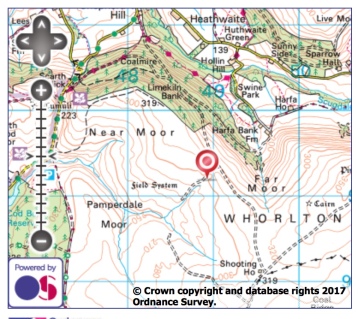

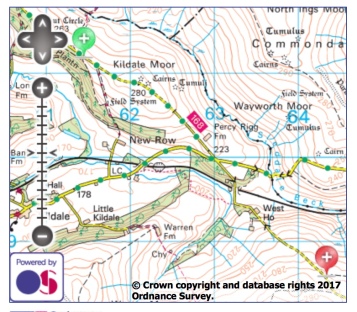

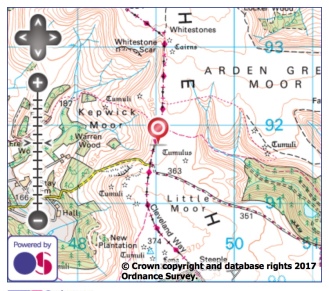

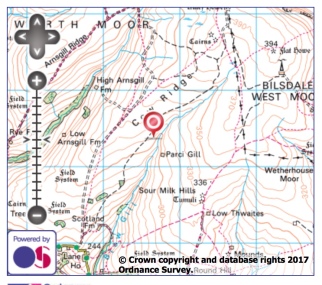

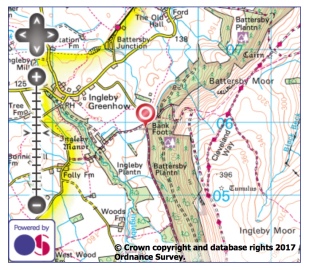

And at great expense, I have rebranded the new site (I had a few comments about the yellow background) so it’ll now be minimalist white. Hosting the site on my own domain will also mean I can utilise the OS mapping better rather than just inserting a screen grab. Watch this space as they say. Or rather watch the new space.

I think I’ve migrated the whole of the archive over to the new domain but if you come across any oddity please let me know.

Thanks for your support over the years. I hope it continues with the new site. And don’t forget “fhithich” is Gaelic for raven and is pronounced the same as its call!

You must be logged in to post a comment.