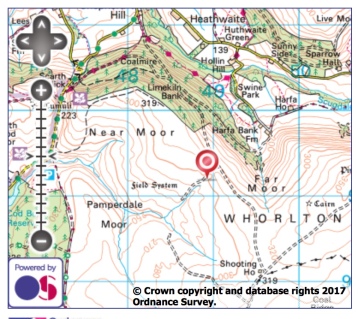

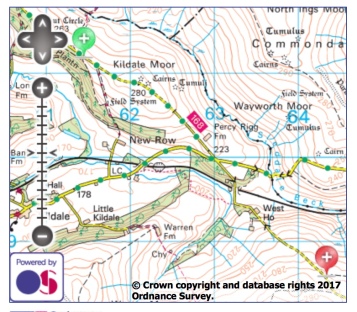

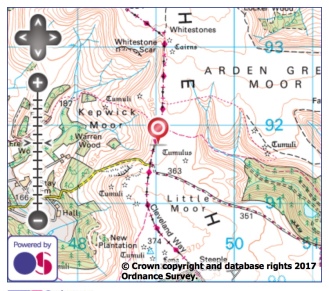

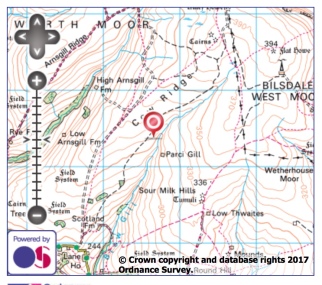

It must have needed a torrent of water to have carved this gill on Pamperdale Moor near Osmotherley. Certainly not water from the spring mapped as Holy Well and situated way down the gill not far to its junction with Crabdale Beck. The “spring” in the photo, higher up, doesn’t even qualify with an Ordnance Survey symbol. It’s just a sodden patch of chalybeate stained moss. Behind me the now dry gill continues upwards culminating in a notch on Stoney Ridge with Scugdale. And there lies the clue, for at the time of the last ice age Scugdale was dammed by the glacier and was full to the brim with water. But at some time the narrow ridge gave way releasing millions of gallons of water from Lake Scugdale and carving the gill.

You must be logged in to post a comment.