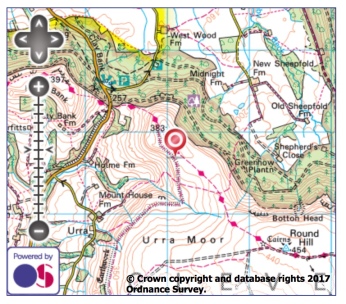

Along the eastern edge of upper Bilsdale is a linear prehistoric dyke almost four and a half kilometres long. In the photo the can be made out on the left curving down to Bilsdale Beck as a bilberry topped embankment with a ditch on the down slope filled with bracken. From the beck the dyke rises then contours around the escarpment. The embankment is up to 3.5m wide in places and typically half a metre high. It is faced with stone in places. The ditch is a maximum 3m wide, half a metre deep and in places cut into the sandstone bedrock.

Similar dykes on the North York Moors are considered to be Middle Bronze Age which dates it to 1500–1200 BC. Other local names for the Urra Moor dyke are Billy’s Dyke, Cliff Dyke and Cromwell’s Lines. The former I guess a reference to the often repeated legend that William the Conqueror lost his way on the approaches to Bilsdale in his harrying of the North thus giving rise to the dale’s name although a more likely explanation is that Bilsdale derives from the old Norse name Bildr.

For what purpose the dyke was built for no one is sure. Defence? Stock enclosure? Prestige? Its construction must have taken a lot of resources so it would certainly have marked an important boundary. Perhaps a warning to those about to enter a tribe’s territory.

You must be logged in to post a comment.